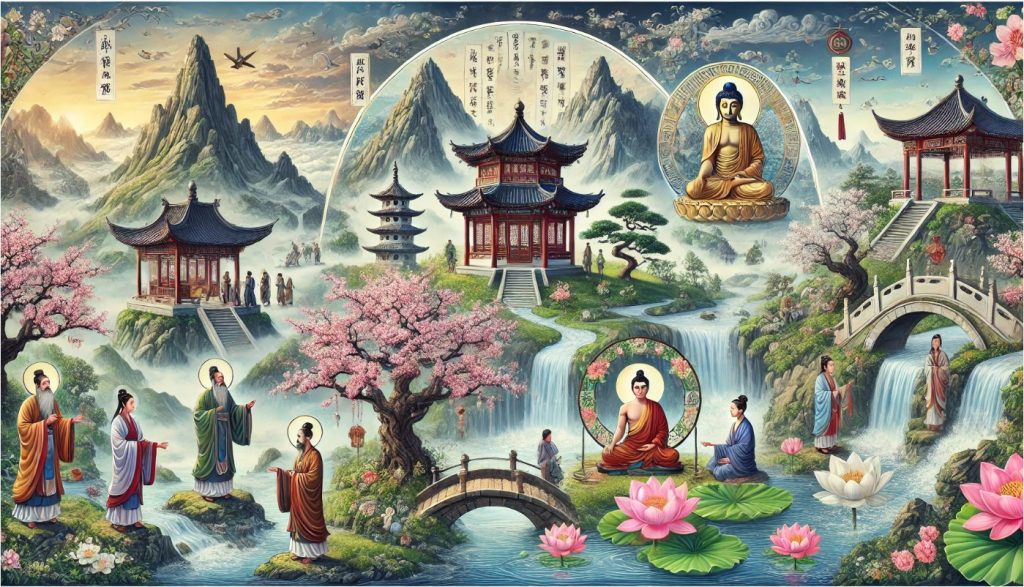

Chinese philosophy is a rich and diverse intellectual tradition that has shaped Chinese culture, politics, and society for over two millennia. Among the most influential schools of thought in Chinese philosophy are Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. Each of these traditions offers a unique perspective on life, ethics, and the nature of the universe. While Confucianism focuses on moral values, social harmony, and the role of individuals within society, Taoism emphasizes the importance of living in accordance with the natural world, and Buddhism introduces concepts such as impermanence, suffering, and enlightenment. Together, these three philosophical systems form a crucial part of Chinese intellectual and spiritual history, influencing everything from governance and education to personal conduct and spiritual practice.

Taoism: The Path of Harmony with Nature

Origins and Key Texts

Taoism (or Daoism) is an ancient Chinese philosophical and spiritual tradition that traces its origins to the legendary figure of Laozi (Lao Tzu), a philosopher and sage who is traditionally credited with writing the Tao Te Ching, one of the foundational texts of Taoism. The Tao Te Ching, which translates to “The Classic of the Way and Virtue,” provides a profound exploration of the concept of the Tao (the Way), emphasizing the importance of simplicity, humility, and living in accordance with the natural flow of the universe. Taoism is often characterized by its focus on harmony, balance, and the inherent spontaneity of nature.

Another key text in Taoism is the Zhuangzi, attributed to the philosopher Zhuang Zhou (also known as Chuang Tzu), which is filled with stories, parables, and metaphysical discussions. The Zhuangzi takes a more playful and allegorical approach than the Tao Te Ching, using humor and paradox to explore ideas such as the relativity of truth and the fluidity of life.

Taoism’s core philosophy is based on the idea of wu wei, or “non-action.” This concept does not refer to laziness or inaction but rather the art of achieving things without force or struggle, aligning one’s actions with the natural flow of the universe. Taoism teaches that by cultivating this state of non-attachment and non-forcing, one can live a life of tranquility and balance.

The Concept of the Tao

The Tao is a central concept in Taoism. It is understood as the fundamental force or principle that underlies the natural world and all existence. The Tao cannot be defined in concrete terms, as it is considered beyond language and comprehension. In the Tao Te Ching, Laozi writes, “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name,” underscoring the ineffable and mysterious nature of the Tao.

The Tao is not a deity but rather an abstract principle that governs the universe. It represents the natural order of things, an unspoken flow that sustains harmony and balance in the world. Everything in the universe, from the stars and planets to the movements of animals and the behavior of human beings, is believed to be governed by the Tao. To live in accordance with the Tao is to live harmoniously, without forceful interference or excessive striving.

The Role of the Sage and Immortality

In Taoism, the sage is a person who has mastered the art of living in harmony with the Tao. The sage embodies the virtues of humility, wisdom, and simplicity. Laozi and Zhuangzi both describe the sage as someone who lives a life of effortless action (wu wei), understanding the deep, hidden rhythms of the universe and aligning their actions with those rhythms.

A significant aspect of Taoist practice is the pursuit of immortality, although this concept is more philosophical than literal. Taoist immortality is not about physical survival but about the cultivation of spiritual longevity, achieved through practices such as meditation, qigong, and alchemy. Taoist alchemists believed that by refining the body and spirit, one could achieve a state of eternal vitality, transcending the cycle of birth and death.

Taoist Practices and Influence

Taoist practices are aimed at aligning individuals with the Tao and achieving a balanced and harmonious life. These practices include meditation, tai chi, qigong, and feng shui. Taoism also incorporates rituals and the worship of deities in the context of religious Taoism, which developed over time alongside philosophical Taoism.

Taoism’s influence on Chinese culture is profound, shaping not only spiritual and philosophical life but also Chinese medicine, art, literature, and politics. The Taoist idea of harmony with nature has influenced environmental thinking in China, as well as concepts of health and wellness.

Confucianism: Ethics, Social Harmony, and Moral Duty

The Teachings of Confucius

Confucianism, founded by the philosopher Confucius (Kong Fuzi, or Kongzi, 551–479 BCE), is a system of moral and ethical philosophy that focuses on social relationships, virtue, and the cultivation of personal character. Confucius believed that the key to a harmonious society lay in cultivating ren (仁), which is often translated as “benevolence” or “humaneness.” According to Confucius, human beings should strive to act with kindness, compassion, and empathy toward others, cultivating moral virtues in their daily lives.

The core teachings of Confucianism are encapsulated in the Analects of Confucius, a collection of sayings, dialogues, and thoughts compiled by his disciples. The Analects discuss various aspects of life, such as proper conduct, the relationship between rulers and subjects, family dynamics, education, and the importance of self-cultivation.

The Five Relationships

One of the central aspects of Confucian philosophy is the emphasis on the importance of social relationships. Confucius identified five key relationships that form the basis of a harmonious society:

- Ruler and Subject: The relationship between the ruler and the people should be based on mutual respect and benevolence. A ruler should act with virtue and wisdom, while the subjects should show loyalty and obedience.

- Father and Son: Filial piety is one of the core values in Confucianism. The father is responsible for guiding and nurturing the son, while the son owes respect and obedience to the father.

- Husband and Wife: The relationship between husband and wife should be one of mutual respect, with each fulfilling their roles in the family structure.

- Older Brother and Younger Brother: The elder sibling is responsible for guiding and supporting the younger, while the younger should respect and follow the example of the older.

- Friend and Friend: The relationship between friends is based on mutual respect, trust, and equality.

These relationships are based on the principles of li (礼), which refers to the proper conduct, rituals, and manners that govern social interactions. Confucius believed that by adhering to these principles, individuals could cultivate their moral character and contribute to the well-being of society.

The Role of Education and Self-Cultivation

Education plays a central role in Confucianism. Confucius believed that education was the key to personal and moral development, and he advocated for a system of learning that emphasized not just academic knowledge but the cultivation of virtue. The concept of self-cultivation (修身, xiūshēn) is fundamental to Confucian thought. It refers to the process of continuously improving oneself through reflection, study, and the practice of virtuous behaviors.

Confucianism holds that the cultivation of virtue is not a one-time event but a lifelong process. Through education and self-cultivation, individuals can align themselves with the moral order of the universe, creating a more harmonious society.

Confucianism and Governance

Confucianism has a deep influence on Chinese political thought. Confucius believed that the ruler’s primary responsibility was to govern by virtue and lead by example. A wise and virtuous ruler would inspire loyalty and respect from the people, and the people, in turn, would live according to Confucian values. Confucianism thus emphasizes the importance of moral leadership and the role of government in promoting social harmony.

Confucian thought also influenced the imperial examination system, which was used to select government officials based on merit rather than birthright. The exams focused on knowledge of Confucian texts and principles, ensuring that officials were educated in moral and ethical matters.

Buddhism in China: The Path to Enlightenment

The Introduction of Buddhism to China

Buddhism, a religious and philosophical tradition that originated in India around the 6th century BCE, was introduced to China via the Silk Road around the 1st century CE. The teachings of Sakyamuni Buddha (the historical Buddha) emphasized the impermanence of life, the nature of suffering (dukkha), and the possibility of overcoming suffering through the attainment of nirvana—a state of enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of birth and death (samsara).

Initially, Buddhism was met with resistance in China, as it conflicted with traditional Confucian values and Taoist beliefs. However, over time, Buddhism became increasingly integrated into Chinese culture, particularly during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), when it gained imperial patronage and experienced a period of flourishing.

Core Teachings of Buddhism

The core teachings of Buddhism are encapsulated in the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The Four Noble Truths explain the nature of suffering and its cessation:

- Dukkha: Life is inherently suffering due to impermanence.

- Samudaya: The cause of suffering is attachment, desire, and ignorance.

- Nirodha: It is possible to end suffering by eliminating attachment and desire.

- Magga: The way to end suffering is by following the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path outlines a practical guide to ethical and mental development, including right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. By following this path, an individual can cultivate wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline, ultimately leading to enlightenment.

Buddhist Sects in China

In China, Buddhism evolved into several distinct schools, including Chan Buddhism (which later became Zen in Japan), Pure Land Buddhism, and Tian Tai Buddhism. Each of these schools emphasizes different aspects of the Buddhist path, such as meditation (Chan), devotion to Amitabha Buddha (Pure Land), or the study of scriptures and philosophy (Tian Tai).

The Influence of Buddhism on Chinese Culture

Buddhism has had a profound impact on Chinese culture, influencing art, literature, politics, and daily life. Buddhist temples, monasteries, and statues are found throughout China, and Buddhist philosophy has shaped Chinese views on life, death, and the afterlife. Buddhist practices such as meditation and chanting have become integrated into Chinese spiritual life, and Buddhist ideas about compassion, karma, and reincarnation have been widely embraced.

Through its interactions with Taoism and Confucianism, Buddhism also contributed to the development of Chinese syncretism, where elements of these three philosophies merged to create a unique spiritual worldview that continues to influence Chinese thought and practice today.

The Integration of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism

In Chinese history, Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism have not been separate or antagonistic traditions; rather, they have often interacted and influenced each other in complex ways. Many Chinese people practice elements of all three systems simultaneously, embracing Taoist ideas of natural harmony, Confucian ethics of family and social duty, and Buddhist teachings on the impermanence of life and the pursuit of enlightenment.

This blend of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism has contributed to the rich diversity of Chinese philosophy and spirituality, creating a harmonious synthesis of ideas that has shaped Chinese civilization for millennia.