The One-Child Policy was one of the most significant social engineering policies ever implemented in modern history. Introduced by the Chinese government in 1979, the policy aimed to control China’s rapidly growing population and address the economic challenges associated with overpopulation. For over three decades, it reshaped the demographic, economic, social, and cultural fabric of the nation. Though the policy was officially relaxed in 2016, its long-term impacts are still being felt in various aspects of Chinese society.

The Origins and Implementation of the One-Child Policy

The Economic and Demographic Context of the 1970s

In the 1970s, China was undergoing a period of immense transformation. After the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Chairman Mao, the Chinese government sought to stabilize the country’s population growth, which was seen as a major barrier to economic development. At the time, China’s population was growing at an alarming rate, and the government feared that this unchecked growth would exacerbate food shortages, strain resources, and hinder economic progress.

- Famine and Scarcity: The Great Famine (1959–1961), caused by a combination of poor policy decisions and natural disasters, left a lasting scar on China’s population. With an agrarian economy still in place, the government viewed population control as a necessity for economic recovery and development.

- Family Planning: In the late 1970s, China’s leadership, under Deng Xiaoping, introduced various family planning measures to curb the population growth rate. Initially, these measures were voluntary, but they soon gave way to more forceful, state-driven policies, leading to the formal implementation of the One-Child Policy.

Policy Implementation and Enforcement

The One-Child Policy was officially launched in 1979, with the goal of limiting most families to having only one child. This policy was enforced through a range of mechanisms, including economic incentives, social pressures, and, at times, coercive measures. The policy’s enforcement was more strict in urban areas, where the government had more control, while rural areas were granted some exceptions.

- Urban vs. Rural Differences: In cities, the policy was rigorously applied, and families who violated the policy were subject to fines and penalties. However, rural families were often allowed to have a second child, particularly if the first child was a girl. This was due to the traditional preference for male children in rural farming communities, where boys were seen as vital for agricultural labor.

- Incentives and Penalties: Families that complied with the policy received benefits such as financial incentives, free education, and access to better housing. Conversely, those who violated the policy faced fines, loss of social benefits, and in some cases, forced abortions or sterilizations.

- State Control and Monitoring: The government established a vast network of family planning officials and health workers who were tasked with monitoring reproductive behavior, performing regular checks, and ensuring compliance with the policy.

Relaxation of the Policy

In the early 21st century, as China’s demographic structure began to shift, the One-Child Policy started to face increasing criticism. Concerns about an aging population, a shrinking workforce, and the negative consequences of the policy on social welfare prompted the government to gradually ease the restrictions.

- The Two-Child Policy: In 2016, the Chinese government officially ended the One-Child Policy, allowing all couples to have two children. This was a response to the mounting pressure of an aging population and the desire to increase the birth rate.

- The Three-Child Policy: In 2021, the government introduced a new policy allowing families to have up to three children, coupled with additional incentives to encourage childbearing, including tax breaks, housing benefits, and improved maternity care.

Social and Demographic Impacts of the One-Child Policy

Population Aging and Gender Imbalance

One of the most significant long-term impacts of the One-Child Policy has been the demographic shift it caused, particularly in terms of population aging and gender imbalance.

- Aging Population: As a result of the policy, China’s birth rate plummeted, leading to a rapidly aging population. According to government statistics, by 2020, more than 18% of the population was over 60 years old. The shrinking working-age population has placed a strain on social services, pensions, and healthcare systems, leading to concerns about the country’s ability to support its elderly citizens.

- Gender Imbalance: The One-Child Policy exacerbated China’s long-standing preference for male children, leading to a significant gender imbalance. In some areas, this preference for sons led to sex-selective abortions, female infanticide, and the abandonment of girls. This has resulted in millions more men than women in China, creating significant social challenges, including difficulty for men to find marriage partners, a phenomenon often referred to as the “leftover men.”

The “4-2-1” Family Structure

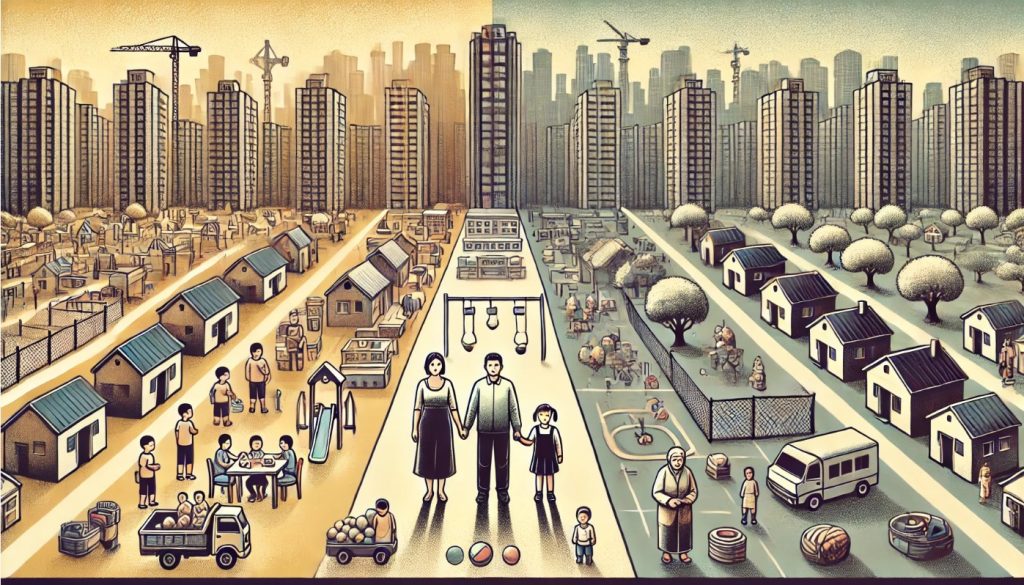

The One-Child Policy has also had a profound effect on family structures in China. The traditional extended family model, with multiple children and extended kin, was replaced by the “4-2-1” structure, where one child has two parents and four grandparents.

- Parental Pressure: Only children are often under immense pressure to succeed academically and professionally, as they are the sole hope for continuing the family line and supporting their aging parents. The psychological burden of being the only child, combined with high academic expectations, has contributed to mental health challenges among Chinese millennials.

- Care for the Elderly: With fewer children to care for aging parents, the One-Child Policy has also placed a strain on the filial piety system, which traditionally emphasizes children’s responsibility for caring for elderly parents. As China faces an increasing number of elderly people with fewer caregivers, the government is grappling with how to provide social services for an aging population.

Economic Consequences of the One-Child Policy

Workforce Shortages and Economic Growth

In the decades following the implementation of the One-Child Policy, China’s economy boomed, benefiting from an abundant and relatively cheap labor force. However, the long-term effects of a declining birth rate have begun to threaten the sustainability of this growth.

- Labor Force Decline: The One-Child Policy, coupled with improvements in life expectancy, has led to a shrinking working-age population. As the number of young people entering the workforce declines, the supply of labor is expected to decrease, potentially leading to higher labor costs and reduced productivity.

- Wages and Employment: As the labor market tightens, companies may face increased difficulty in recruiting workers, which could drive up wages. However, this may also lead to automation and other technological solutions to maintain productivity.

- Economic Transition: The Chinese government is now focusing on transitioning the economy from one driven by cheap labor and manufacturing to one focused on high-tech industries, innovation, and services. This transition, however, is complicated by the demographic challenges posed by the One-Child Policy.

The Rise of the “4-2-1” Economic Model

The “4-2-1” family structure has also had a significant impact on China’s consumer market. As only children grow older and begin to assume financial responsibility for their parents and grandparents, they face increased economic pressure.

- Elderly Care: With fewer children to provide for aging relatives, the responsibility for elderly care falls more heavily on the only child. This has led to a growing demand for elder care services, such as nursing homes, home healthcare, and elder-friendly infrastructure.

- Consumer Behavior: The economic pressures faced by only children have influenced their spending habits. Many young adults are financially burdened by their role as the sole provider for their families, which affects their ability to invest in personal goals such as buying a home or starting a business. However, these young adults also represent a key market for goods and services targeted at the middle class, including healthcare, luxury goods, and financial planning services.

Social and Cultural Effects

The Psychological Impact on Only Children

Growing up as an only child in a society that placed a strong emphasis on academic achievement and success has had a profound psychological impact on many millennials and younger generations in China.

- Pressure to Succeed: Only children often face significant pressure from their parents to excel academically and professionally, as they are the only child responsible for the family’s future. This has contributed to a rise in mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and burnout, particularly among young adults.

- Isolation and Social Development: Some only children report feelings of loneliness and isolation, particularly in the absence of siblings. Without siblings to share experiences or help care for aging parents, the emotional burden of being the only child can be overwhelming.

- Changing Attitudes Toward Family: While the One-Child Policy has fostered a sense of individualism, it has also led to shifts in how Chinese millennials view family life. Many younger adults are more likely to prioritize career success, personal fulfillment, and independence over traditional family structures and responsibilities.

Shifting Gender Norms and Family Expectations

The gender imbalance created by the One-Child Policy has contributed to shifting gender norms in China. Women, in particular, have increasingly gained access to education and the workforce, leading to changes in family dynamics.

- Women’s Empowerment: With more women in the workforce and a higher level of education, gender roles are gradually evolving. Women are now delaying marriage and childbirth in favor of career advancement, and the expectations placed on women in the traditional family structure are slowly diminishing.

- Marriage and Fertility Trends: The gender imbalance has also affected marriage rates, with many men finding it difficult to secure a partner due to the shortage of women. This has led to delayed marriages and a decline in fertility rates, further compounding China’s demographic challenges.

Legacy and Future Challenges

While the One-Child Policy was formally relaxed in the 2010s, its long-lasting effects will continue to influence China’s demographic, economic, and social landscape for decades. The country now faces a range of challenges, including an aging population, a shrinking workforce, and the psychological and economic impact on the only children raised under the policy.

- Population Decline: Despite the policy’s relaxation, the birth rate in China has remained low. Many young couples are choosing not to have more than one or two children due to the high cost of living, pressure to succeed, and changing attitudes toward family life. This has raised concerns about future population decline and its potential economic consequences.

- Sustainable Economic Growth: The government must find ways to sustain economic growth without relying on an abundant labor force. This includes investing in automation, innovation, and services, as well as developing policies to encourage a more balanced demographic profile.

- Social Services for the Elderly: With a rapidly aging population, China will need to invest significantly in healthcare, pensions, and elder care services. This will require balancing economic growth with social welfare policies to support the elderly.

The One-Child Policy, while achieving its goal of reducing population growth, has left China with a complex demographic and social legacy. As the country moves forward, it will face the challenge of addressing the consequences of this policy while adapting to new realities in a rapidly changing world.